Review: DANCING AT LUGHNASA at National Theatre Olivier

Brian Friel’s 1990 play set during harvest time at the village of Ballybeg somewhere in County Donegal, is intensely evocative of a world which has almost entirely disappeared. At the home of the five Mundy Sisters before the onset of the Second World War, there’s a daily battle to make ends meet whilst looking after the men in their lives — Uncle Jack (Ardal O’Hanlon) just returned from the leper colony in Ugandaand seven year old Michael Evans whose childhood memories recounted as an adult (Tom Vaughan-Lawlor) serve to narrate the piece.

Siobhán McSweeney (Maggie), Bláithín Mac Gabhann (Rose), Louisa Harland (Agnes), Justine Mitchell (Kate) & Alison Oliver (Chris) in Dancing at Lughnasa at the National Theatre. Photo by Johan Persson

Siobhán McSweeney (Maggie), Bláithín Mac Gabhann (Rose), Louisa Harland (Agnes), Justine Mitchell (Kate) & Alison Oliver (Chris) in Dancing at Lughnasa at the National Theatre. Photo by Johan Persson

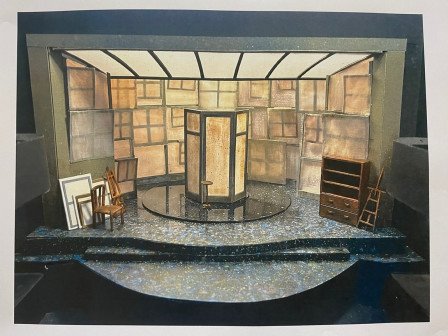

On Robert Jones’ calm-inducing pastoral stage, a path meanders past the cottage garden and up to a cornfield before disappearing out of sight. Down centre, the kitchen with its faltering radio, serves as the centrepiece to the set where discussions, dancing and arguments punctuate the peaceful rural idyll in Josie Rourke’s cocooning production ranged across the immense Olivier stage.

In truth, the play has little of note to say and few dramatic statements to make, yet the familial interactions and the personalities they illuminate are utterly captivating. Each character is fully formed with their own foibles and idiosyncrasies. Chris (Alison Oliver) the young unmarried mother is still in love with the boy’s father Gerry (Tom Riley) who makes occasional visits, bringing a light but fleeting frivolousness to their lives. Agnes (Louisa Harland) also clearly harboured feelings for Gerry creating undertones of unspoken tension. Meanwhile Maggie (Siobhán McSweeney) anchors everyone and neutralises frictions with her playful jocularity and riddles, most especially acting as a foil to Kate’s (Justine Mitchell) constant lecturing and devout upbraiding of her wayward sisters. Finally, perpetually adorned with wellies Rose (Bláithin Gabhann), casts them off in the hope of finding some kindness and companionship when all would attempt to dissuade her of such an aspiration.

The title of the piece is derived from a pagan Irish festival in honour of god Lugh in thanks for his delivery of a good harvest and bilberries growing in wild hedgerows around the same time each year. From this production, it is quite easy to believe that the events and simple pleasures conveyed from the summer of 1936 could go on forever, but the narration reveals the mixed fortunes of each character as the play draws gently to a close.

Latest News

INTO THE WOODS releases behind-the-scenes photos in honour of 11 Olivier Award nominations and 100 performances

6 March 2026 at 18:33

INTO THE WOODS releases behind-the-scenes photos in honour of 11 Olivier Award nominations and 100 performances

6 March 2026 at 18:33

Production photos released for the UK and Ireland tour of MEAN GIRLS THE MUSICAL

6 March 2026 at 18:24

Production photos released for the UK and Ireland tour of MEAN GIRLS THE MUSICAL

6 March 2026 at 18:24

Critics’ Circle Theatre Awards 2026

6 March 2026 at 16:45

Critics’ Circle Theatre Awards 2026

6 March 2026 at 16:45

In the rehearsal space with the creative team for A MIRRORED MONET

6 March 2026 at 16:26

In the rehearsal space with the creative team for A MIRRORED MONET

6 March 2026 at 16:26