Review of the National Theatre's Medea

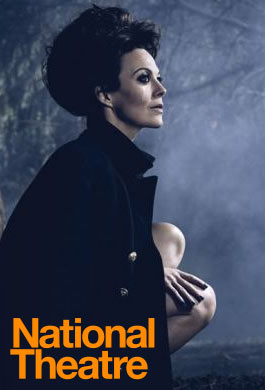

There’s good news and bad news about this National Theatre production of an ancient Greek drama, starring Helen McCrory.

There’s good news and bad news about this National Theatre production of an ancient Greek drama, starring Helen McCrory.

The good news is McCrory herself who gives a gripping performance as an exiled queen driven to murder; the bad news is the adaptation by Ben Power, who makes some odd choices which in my opinion weakens this critically acclaimed revival.

Medea, her husband Jason and their two sons have washed up in a hostile kingdom following their famous adventures with the Argonauts. But while the mood of Jason and the Argonauts is fun and sunny this is a much darker work.

Jason persuades himself that the best way of achieving security for his sons is to marry in to the Royal family. Medea is heartbroken at her lover’s perceived betrayal and plots the destruction of key players in her humiliation, culminating in an horrific double murder.

The original author, Euripides, opens with an established family set-up for the exiles, including a tutor for the two little sons. Medea, we’re told is weeping and wailing at the news of Jason’s marriage. The King appears to be lenient but it then becomes clear that the kid’s lives are in danger from his regime.

McCrory herself gives a gripping performance as an exiled queen driven to murder

Ben Power ditches most of this crucial detail and opens with a monologue in which the family nurse describes, amongst other things that Medea has already killed her little brother for Jason’s love. As a result a play that’s usually taut with the tension of "can she commit murder?" is diminished, as we already know she’s an impassioned child killer. So it simply becomes about when she’ll do it rather than will she do it.

The production is in modern dress so we first encounter her dressed like Ripley from the film Alien, dragging determinedly on a cigarette and howling and growling. There’s no doubt this woman is quite capable of murdering anyone as mercilessly as the way in which we’ve just heard she dispatched her younger brother.

It would seem impossible to maintain that level of ferocity throughout but with Ben Power denying her the chance to change from impassive grief to murderous rage she’s obliged to try and succeeds brilliantly. I just wish she’d been given the chance to show us the subtle mental shits that turn an emotional wreck into a purposeful killer.

In this production her family are barely unpacked, holed up in some, formally grand, subterranean basement so the family are already outcasts and there’s no sense of the nail-biting disintegration of their status which Euripides intended.

As befits these changes McCrory is obliged to play a caged tiger right from the starts not a grief stricken, wronged woman who gets a shocking idea and follows it through.

It’s a lucky by-product of a rather weak performance by the actress playing the family nurse, who delivers an opening précis of the story so far, that McCrory shines, by comparison, from her first line.

The set is rather odd. The architecture suggests some abandoned hotel lobby from a war zone similar to the pictures we see on the TV news from Syria or Gazza etc but it opens out on to a very northern European looking forest. There’s no sense of the hot oppressive atmosphere of Greece. A chorus of women, speaking and moving in unison, gather in picturesque groups around the place, twitching and writhing in a way that’s rather too self-consciously inspired by the fashionable choreographer Pina Baush.

All credit then to McCrory who takes all these handicaps in her stride and just ploughs through events in a non-stop murderous rage.

Visiting characters, like the king, an old family friend and Jason himself, who drop in to reveal the plot developments which usually mark the gear changes in Medea’s mind, are weekly performed. Poor Danni Sapani as her husband is even directed to deliver key parts of his performance with his back to us.

The death of a princess, horrifically described in the text is here illustrated by an underwhelming piece of interpretive dance which doesn’t satisfy in conveying very much horror at all.

A star performance then in an otherwise mis-judged production of a dodgy adaptation. The muddle around her makes Helen McCrory’s achievement all the greater.

Latest News

Review: BLINK at the King's Head Theatre

13 March 2026 at 20:00

Review: BLINK at the King's Head Theatre

13 March 2026 at 20:00

Review: TURN IT OUT WITH TILER PECK AND FRIENDS at Sadler’s Wells

13 March 2026 at 16:01

Review: TURN IT OUT WITH TILER PECK AND FRIENDS at Sadler’s Wells

13 March 2026 at 16:01

Review: ANCIENT GREASE at The Vaults

13 March 2026 at 11:19

Review: ANCIENT GREASE at The Vaults

13 March 2026 at 11:19

Review: AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL: CHAPTER 1 at King's Head Theatre

13 March 2026 at 11:12

Review: AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL: CHAPTER 1 at King's Head Theatre

13 March 2026 at 11:12