Review: A PACIFIST'S GUIDE TO THE WAR ON CANCER at the National Theatre

Cancer is a very emotive subject. It touches most of our lives in a deeply traumatising way. It certainly has touched mine so how you react to this musical will probably be informed by how raw you’re feeling. It could be that the cathartic experience of watching a show, any show about cancer, no matter how crudely assembled, will be enough to move you and allow you to over look its considerable flaws. I wasn’t moved, I grew increasingly alienated by its attempts to make excuses for its short comings and to justify itself whilst bullying me to tears and daring me not to be moved.

Cancer is a very emotive subject. It touches most of our lives in a deeply traumatising way. It certainly has touched mine so how you react to this musical will probably be informed by how raw you’re feeling. It could be that the cathartic experience of watching a show, any show about cancer, no matter how crudely assembled, will be enough to move you and allow you to over look its considerable flaws. I wasn’t moved, I grew increasingly alienated by its attempts to make excuses for its short comings and to justify itself whilst bullying me to tears and daring me not to be moved.

It begins with a preposterous voice over from the writer and director Byrony Kimmings which rebukes us for not talking enough about death, which is utter nonsense; were she to turn on the TV any evening she could find heart breaking documentaries about hospitals and emergency services, drama (good and bad) in which death is a major plot point or motivating force and of course news reports of death from every corner of the world. Were she to go to the theatre I’d say at least 50% of plays, going right back to the ancient Greeks deal with death. And there can’t be a family on earth that hasn’t dealt with the death of a relative and very few individuals have never been to a funeral or visited a hospital. She then insults us by claiming we’d only find the subject palatable if it were presented as a “nutty weirdo” musical (in the programme she tells us she’s not a fan of them, plus she’s seldom made work for more than one performer at a time)

Two thirds of what follows tells the story of a mother, Emma, and her experiences during 12 hours waiting in a hospital whilst her baby undergoes tests for cancer. It’s revealed that Kimmings herself has a sick child – daring us not to be moved or question the authenticity of what she shows us. I'm going to question it. Do hospitals really announce your baby’s progress over the public address system or yell it at you as they wheel trolleys around?

As Emma waits her nightmare situation, and that of other cancer patients, is expressed using crude, A level Theatre Studies, physical theatre techniques.

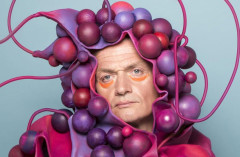

The rest of the hospital lumber around her like zombies, or like zombies lit in red at night, the patients are pursued by actors dressed up in sparkly lumpy costumes to represent cancer cells and the stage fills up with oppressive inflatable shapes. Sometimes people sing awful songs, with pedestrian melodies and lyrics which don’t even approach the complexity of grieving or fear of suffering.

I did admire Lewis Gibson’s sound design which effectively represented the click of heals down a lonely hospital corridor or the sludge of voices you hear when you’re in shock.

Just before the final third of the show we get another voice over from Kimmings admitting it’s impossible to make a cancer show that does the subject justice. Well, that was certainly true in her case.

It’s not her fault; she’s woefully under qualified as a practitioner to even attempt it, which begs the question, why the National Theatre and Complicite commissioned her to work way out of her comfort zone and experience. What a shame they didn’t commission the team that created LONDON ROAD, the national theatre’s recent, daring and haunting musical about a town scarred by rape and murder.

The final third utilises every cheap trick in the book to dare you not to cry, the actors mime to real people relating their experiences, cancer patients are brought up on stage, the audience are asked to call out names of anyone they know who’s been affected by cancer, there’s a sing a-long to a particularly crap song and more voice overs from Kimmings excusing and justifying herself.

We could use a great show that dealt with cancer. This isn’t it. It’s ghastly!

Latest News

Review: LANDSCAPES at Sadler's Wells East

12 March 2026 at 10:31

Review: LANDSCAPES at Sadler's Wells East

12 March 2026 at 10:31

Is THE GREATEST SHOWMAN THE MUSICAL coming to the West End?

11 March 2026 at 16:52

Is THE GREATEST SHOWMAN THE MUSICAL coming to the West End?

11 March 2026 at 16:52

Review: MANIC STREET CREATURE at Kiln Theatre

11 March 2026 at 10:33

Review: MANIC STREET CREATURE at Kiln Theatre

11 March 2026 at 10:33

Rehearsal images released for AVENUE Q at the Shaftesbury Theatre

10 March 2026 at 17:23

Rehearsal images released for AVENUE Q at the Shaftesbury Theatre

10 March 2026 at 17:23