Review: THE MILK TRAIN DOESN’T STOP HERE ANYMORE at Charing Cross Theatre

Tennessee Williams’ considerable output during his lifetime, ensures that his name is rarely out of the West End, but whereas The Glass Managerie, Cat On A Hot Tin Roof and A Streetcar Named Desire (among others) are frequently dusted-off, Milk Train… is a far less frequently observed beast, despite containing some of the playwright’s more personal musings on mortality and longing.

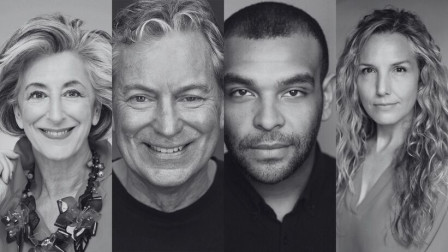

Sara Kestelman and Sanee Raval in The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore. Photo Nick Haeffner

Sara Kestelman and Sanee Raval in The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore. Photo Nick Haeffner

It is believed that when former actor Frank Merlo (the man largely credited with helping Williams wean himself off a life of casual sex and prescription drugs) died of lung cancer aged 42, the playwright set to work on the piece as a conduit for his own grief. In the play, he includes the role of Blackie, a frank and feisty, long-suffering secretary/personal assistant perhaps as a nod to Merlo’s 15 fractious years spent by his side as lover, manager and confidant.

Set at a villa amidst the splendour of an exclusive enclave of estates populated by the ageing ultra-rich of the Amalfi Coast, Flora Sissy Gosforth (Linda Marlowe) dictates her memoirs to her recently widowed young secretary Blackie (Lucie Shorthouse). Widowhood is possibly the only commonality the women share, Sissy having endure the state on no fewer than four occasions, accumulating wealth as each successive husband was laid to rest. Into this potentially stagnant mix, otherwise only populated by a small retinue of rarely seen staff, is introduced the slightly mystic figure of Christopher Flanders (Sanee Ravel)a handsome poet no longer in the first flush of youth, who has gained an unfortunate reputation as The Angel of Death, for being present and somehow assisting those rich elderly expats of his acquaintance as they traverse the final threshold between this life and the next. With limited means of his own, he has endured the ignominy of being generally viewed as a perpetually sponging house guest elsewhere and finally ascends the Amalfi hill, (braving guard dogs in the process), inexplicably drawn to attend Ms Goforth, who he has discerned may be living through the final days of her serious illness.

Wary of his intentions, and refusing his initial requests for an audience, the poet is kept at arms length at one of the guest outhouses in the grounds, whilst Sissy summons renowned ageing socialite and gossip The Witch of Capri (Sara Kestelman) to dinner — amounting to little more than decimation of the drinks trolley — in the hopes of wheedling more damning revelations about her mysterious and uninvited guest.

Certainly strains of classic Tennessee Williams thread through the text, but whilst the supporting characters add colour — particularly Kestelman’s fruity and understated turn (draped in orange, adorned with multitudinous bangles, a turban and a knowing wry sneer) — the central, self-absorbed character of Sissy, the rich, suspicious, ageing society hostess who has grown weary of life, is required to carry the bulk of the play’s themes. It is a tall order, requiring a commanding stage presence and a supremely dominant force of will to pull-off. Large sections of dialogue endow the flawed and vulnerable character with sufficient backstory to imbue the sort of confident life experience found only in the wives of industrialist, diplomats, royalty and perhaps those used to playing them. Here under Robert Chevara’s direction, Ms Marlowe in the central role, largely failed to meet that heady objective, all too often resorting to fidgety mannerisms when a proud and self-assured stillness would have served her better whilst grappling with her lines.

The playing area chosen at Charing Cross Theatre for this production, has also unnecessarily complicated matters for the actors, particularly Ms Marlowe who, (now in her 80s) cannot relish having to grip the arm of a colleague for the several dark and potentially treacherous entrances and exits she is required to undertake during the course of the play.

A valiant attempt to bring one of Williams’ lesser-known works before an audience but the production simply didn’t feel ready on Press Night. This reviewer hopes the cast will grow in confidence as the run progresses.

Latest News

Cast announced for the World Premiere of ALLEGRA

4 February 2026 at 15:02

Cast announced for the World Premiere of ALLEGRA

4 February 2026 at 15:02

Cast announced for European premiere of THE JONATHAN LARSON PROJECT

4 February 2026 at 14:14

Cast announced for European premiere of THE JONATHAN LARSON PROJECT

4 February 2026 at 14:14

Review: LOST ATOMS at Lyric Hammersmith

4 February 2026 at 12:08

Review: LOST ATOMS at Lyric Hammersmith

4 February 2026 at 12:08

I'M SORRY, PRIME MINISTER at Apollo Theatre - Production images released

4 February 2026 at 10:41

I'M SORRY, PRIME MINISTER at Apollo Theatre - Production images released

4 February 2026 at 10:41