Review: SHOWMANISM at Hampstead Theatre

SHOWMANISM — whilst the premise for this one man show is an undoubtedly odd contrivance, it is the very theatricality of the end result, which marks it as an unmistakably inventive and original work.

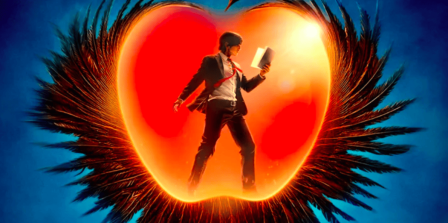

Dickie Beau in SHOWMANISM. Credit Amanda Searle

Dickie Beau in SHOWMANISM. Credit Amanda Searle

Co-created with director Jan-Willem van den Bosch, during the preparation and material gathering phase for his pieces, Dickie Beau interviews individuals, getting them to talk about their lives, careers, and whatever experiences come to mind - here, the anecdotes are loosely connected with acting. Informality appears to be the key, and he offers minimal conversational prompts when something sounds vaguely interesting. Instead, his silence encourages the individual to ramble and wax lyrical about the subject on which they have landed. Familiar voices roll into the less familiar, and with each, Beau imbues his lip-synching performance with human gestures, costumes, props and other artefacts ranged about the stage. One minute he is in a bath, paddling it with a shovel whilst competing for space with the orange tree which is rooted within in it. For much of the performance he strips down, exposing his lithe body adorned only in white underpants. At other moments he jiggles about in a jump suit perched on a chair affixed to the ladder which ascends above and delves below the stage. A conch shell is lowered for a phone conversation, an illuminating kettle serves to boil an egg while toast is made in the back of an upright tape recorder. Yorick’s skull and a spaceman’s helmet compete for attention along with radios and small screens ranged around the playing area. It’s a surrealist’s paradise of prompts.

We hear an earnest yarn about the inhabitants of Oberammergau where the bearded inhabitants commit to ten years of preparations in readiness for their passion play. Ian McKellen’s anecdote is interrupted by workers coming up and down the stairs from the flat above his — “It’s OK, I just wanted to let you know I was here” - he lets float into the temporary silence. His fruity vowels wink at us as he recounts a visit to Laurence Olivier’s widow Joan Plowright, where he encounters the sword used by Edmund Kean as a prop in his portrayal of Richard III. In theatrical circles, the sword has attained some notoriety having been handed down to the great Victorian thesp Sir Henry Irving and on to John Gielgud via his great-aunt the equally revered stage performer Ellen Terry. Gielgud presented it to Olivier after his renowned embodiment of the hunchback but (as McKellen concludes with gentle comic outrage) Olivier clearly decided not to continue the tradition of passing it on! The assumed effrontery serves as a source for some considerable amusement.

A larger than life drag historian, an explorer of mysticism and consciousness, a celebrated Greek cultural advocate, Fiona Shaw, Spitting Image satirist Steve Nallon and even the dour and self-deprecating critic Rupert Christiansen contribute to the steady stream of thoughts and observations. And it is the unprompted candour with which these seemingly insignificant moments are incorporated, which illuminates the inconsequential, distilling their ordinariness into something altogether more fascinating.

Gradually, what initially appears to be little more than a sequence of stand alone monologue vignettes, begin to overlap and double back on themselves maintaining a sense continuity, rhythm and pace to proceedings. The yarns, woven and coalesced into a single individual, reveal themselves a triumph.

SHOWMANISM plays at Hampstead Theatre until 12 July.

Latest News

Full cast announced for London premiere of IN PIECES

26 February 2026 at 16:07

Full cast announced for London premiere of IN PIECES

26 February 2026 at 16:07

DEATH NOTE THE MUSICAL to come to London's Barbican Theatre

26 February 2026 at 11:56

DEATH NOTE THE MUSICAL to come to London's Barbican Theatre

26 February 2026 at 11:56

Review: BITCH BOXER at Arcola Theatre

26 February 2026 at 07:09

Review: BITCH BOXER at Arcola Theatre

26 February 2026 at 07:09

Shakespeare Plays to Watch in London in 2026

25 February 2026 at 23:13

Shakespeare Plays to Watch in London in 2026

25 February 2026 at 23:13