Review: 4.48 PSYCHOSIS at the New Diorama Theatre

Sarah Kane’s final play 4.48 Psychosis has become integrated into theatrical legend since its posthumous premiere in 2000, a delirious expression of depression and suicidal thoughts told through fragmented scenes and evocative poetry.

Sarah Kane’s final play 4.48 Psychosis has become integrated into theatrical legend since its posthumous premiere in 2000, a delirious expression of depression and suicidal thoughts told through fragmented scenes and evocative poetry.

From a playwright whose earlier work had a reputation for startling violence, 4.48 startles not throug hviolence but through the intensity and honesty of its emotions. Eschewing narrative conventions, Kane’s play is presented as a series of vignettes without plot or clear characters, providing significant freedom to directors who choose to tackle it.

Following their site-specific Contractions, deaf-led company Deafinitely Theatre are bringing this unconventional and challenging play to the New Diorama in a production that turns it upside down in more ways than one. Combining sign language with spoken English and projected text, director Paula Garfield has radically reworked Kane’s classic for deaf and hearing audiences alike.

The production’s big concept does more than simply make it accessible; Garfield sees 4.48 as a play about communication, about a struggle to express an unknowable feeling and to relate that feeling to a world incapable of speaking its language. This focus is enhanced by the cast of four male actors, flipping the play around and cleverly associating the deaf struggle with language with the struggle to express often experienced by male sufferers of depression. By combining focuses on deafness and maleness, Garfield evokes a claustrophobic sense of being stuck in one’s own head.

The most thrilling work in this production comes from movement director Alim Jayda, who combines sign language with clowning and mime to create a radical kind of theatrical language which is thoroughly imbued with meaning, both literal and emotional. The best bits of the show are the longer monologues where this stylish choice really gets to shine; Kane’s poetry is projected onto the back walls as actors perform it in blisteringly intense sign language, their entire bodies committed to the physical effort required to express how they feel. These moments are utterly captivating, combing layers of metaphorical meaning with a radical approach to text that feels entirely new.

Frustratingly, the production lurches a bit; in keeping with Kane’s fragmented text, it has a habit of flipping quickly from one idea to another, and there are sections that just don’t work. One militaristic movement sequence derived from the phrase ‘cease this war’ feels a bit forced, and a scene where the two doctors describe the side effects of a series of psychiatric drugs struggles to either disturb or get the laughs it’s clearly trying for. Still, there are other highlights - scenes that forego spoken dialogue and captioning entirely have an unexpected joy to them, and even as the non-BSL speaking sections of the audience are shut out from a literal understanding, the sight of the two deaf ‘patients’ (more halves of the same personality than distinct characters) conversing freely have an authentic flow that evokes a brain nonverbally processing its own emotions.

One of the most unique and difficult things about 4.48 Psychosis is how present its author feels in it. Where typically playwrights seek to create cohesive worlds separate from themselves, the particular circumstances surrounding 4.48 have led to it being seen as a kind of suicide note in theatrical form. That’s a reductive view of the play, but one which speaks to the immediacy which it conjures; the raw authenticity of the play at its best gives one a sense of direct communication with its author. But the bevy of bold and creative choices this production takes have the unfortunate side effect of neutering that appeal; Kane’s voice feels surprisingly absent from the performance.

The greatest mistake this production makes is that it treats 4.48 as a general statement about mental health, rather than as a deeply personal and specific portrait. It’s hard at times not to wish that we were seeing new work from a deaf playwright presented in such a style, as it occasionally feels like Kane’s play is simply along for the ride. Its language is consistently harrowing and beautiful but not always congruous with what the production wants it to be; in broadening the play’s social meaning, it robs it of some of its personal impact.

That social meaning is undeniably powerful, and I can only imagine how much this production will resonate with the deaf community. But I can’t say that it fully tapped into the power of the play. Nevertheless, there’s huge amounts of potential in what Deafinitely Theatre are doing, and I’ll be thrilled to see what they do next.

Latest News

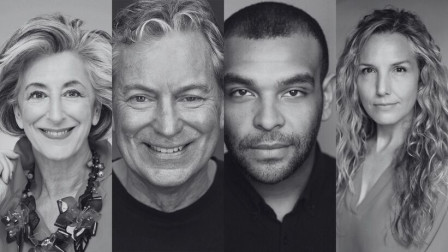

Cast announced for the World Premiere of ALLEGRA

4 February 2026 at 15:02

Cast announced for the World Premiere of ALLEGRA

4 February 2026 at 15:02

Cast announced for European premiere of THE JONATHAN LARSON PROJECT

4 February 2026 at 14:14

Cast announced for European premiere of THE JONATHAN LARSON PROJECT

4 February 2026 at 14:14

Review: LOST ATOMS at Lyric Hammersmith

4 February 2026 at 12:08

Review: LOST ATOMS at Lyric Hammersmith

4 February 2026 at 12:08

I'M SORRY, PRIME MINISTER at Apollo Theatre - Production images released

4 February 2026 at 10:41

I'M SORRY, PRIME MINISTER at Apollo Theatre - Production images released

4 February 2026 at 10:41