Review: THE FUNERAL DIRECTOR at Southwark Playhouse

Iman Qureshi’s moving play about faith, death and sexuality triumphs by finding the potential for empathy amid a tangle of conflicting cultures.

Iman Qureshi’s moving play about faith, death and sexuality triumphs by finding the potential for empathy amid a tangle of conflicting cultures.

Having won this year’s Papatango new writing prize, this second full-length play from writer Iman Qureshi is being debuted at the Southwark Playhouse in a slick production directed by Hannah Hauer-King ahead of a UK tour in March of next year. Set in and around a Muslim funeral directors’ in a divided midlands town, manager Ayesha (Aryana Ramkhalawon) is thrown into an impossible situation when the bereaved Tom (Tom Morley) comes in to arrange a traditional funeral for his deceased boyfriend Ahad.

There’s a fantastic scene at the start where a devastated Tom, in the immediate aftermath of his loss, tries desperately to arrange the funeral as Ahad would have wanted it – but fearing for the impact the community’s reaction could have on their already struggling business, Ayesha and her beleaguered husband Zeyd (Maanuv Thiara) send him across town to Freddy’s Funerals, kicking off a firestorm of legal and cultural battles that threaten to bring them down completely. Simultaneously, the reappearance of old friend Janey (Jessica Clark) brings back feelings that Ayesha thought she’d buried for good.

Qureshi delights in putting characters in the middle of a knotted mess of cultural norms and moral dilemmas and leaving them to figure it out. It’s at its most thrilling when these norms and desires are all overlapping and playing off of each other; a responsibility to one community conflicts with a responsibility to another community conflicts with the fundamental need to be decent to other people conflicts with the financial demands of running a small business. It’s fascinating in its multiplicity, and it’s to the play’s credit that it doesn’t attempt to untangle all this – instead looking for moments of empathy and connection that put it all into perspective.

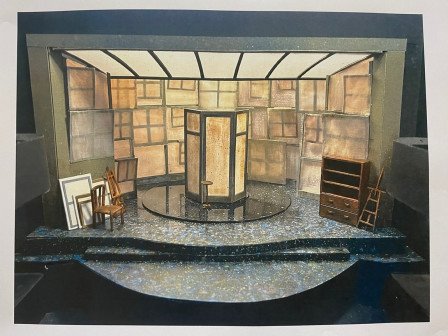

And if there’s one thing that unifies us all – and puts everything into perspective – it’s death, a reality which the play makes effective use of. While the bulk of the play’s action takes place in the pleasant (if a little worn-out) front office of the funeral parlour, a clever design from Amy Jane Cook keeps visible the eerily sterile morgue that’s tucked away behind it, as a constant reminder of mortality. Tom tells Ayesha of his deceased boyfriend’s belief that ‘the only way to change people’s minds was to make them realise we’re just like them’ – it’s a call for empathy that’s poetically mirrored in the play’s thematic grounding in the one way that everyone is the same.

It’s hard not to see that central dilemma as a heightened version of the all-too-common stories you hear about bakeries in the American deep south refusing to make cakes for gay weddings and the like. And it’s a lot easier to demonise those people – perhaps because their white Christianity gives them an assumed cultural power that we wouldn’t automatically attribute to the play’s characters – but the essential dilemma is the same. And as Zeyd shows us, these things make for easily simplified media narratives – ‘Do you think it’s a set up? Daily Mail or something. Heartless Muslims, homophobic Muslims.’ Even their local MP joins the dogpile, blaming the case on Muslims ‘failing to integrate into British culture.’

Like all good drama the play’s fuelled by empathy, and by building it in this way Qureshi dares us to question just how much we’re willing to empathise with the perpetrators of homophobia – and what can be done to bring it to an end. She’s not letting anyone off the hook, but she is engaging with the complex and insidious ways that lifetimes of prejudice can condition people to hate others, and even to hate themselves.

The play ends very abruptly, with an earth-shattering revelation whose consequences aren’t fully given time to sink in, and a very short epilogue that feels like it wraps things up a little too tidily. It might be unfair to say that this tightly built 90-minute play could’ve comfortably gone on for another act – but that desire for more reflects the high quality of what is there. It’s also not particularly formally adventurous – there’s a very striking image at the start, but the rest of it is a fairly conventional series of duologues that don’t leave much room to surprise or wow you. It’s gripping, but you get a pretty clear sense of where this is all headed within the first couple of scenes.

Overall, though, Papatango have dug up a real gem from a very promising writer here – a tear-jerker with a sophisticated and unique voice, containing power that reaches far beyond its morbid setting.

Latest News

INTO THE WOODS releases behind-the-scenes photos in honour of 11 Olivier Award nominations and 100 performances

6 March 2026 at 18:33

INTO THE WOODS releases behind-the-scenes photos in honour of 11 Olivier Award nominations and 100 performances

6 March 2026 at 18:33

Production photos released for the UK and Ireland tour of MEAN GIRLS THE MUSICAL

6 March 2026 at 18:24

Production photos released for the UK and Ireland tour of MEAN GIRLS THE MUSICAL

6 March 2026 at 18:24

Critics’ Circle Theatre Awards 2026

6 March 2026 at 16:45

Critics’ Circle Theatre Awards 2026

6 March 2026 at 16:45

In the rehearsal space with the creative team for A MIRRORED MONET

6 March 2026 at 16:26

In the rehearsal space with the creative team for A MIRRORED MONET

6 March 2026 at 16:26