Review: THE CANE at the Royal Court

THE CANE, my friend Mark Ravenhill’s first major play in 10 years, is about teachers.

Nicola Walker plays Anna, now an adviser for academy schools visiting her ex-teacher mother (Maggie Steed) and father (Alan Armstrong) as his hopes of a retirement celebration are thwarted by the revelation that he used to cane pupils back when it was legal.

Maggie Steed (Maureen) and Nicola Walker (Anna) in The Cane at the Royal Court. Photo credit Johan Persson.

Maggie Steed (Maureen) and Nicola Walker (Anna) in The Cane at the Royal Court. Photo credit Johan Persson.

Improbably the news draws a violent mob to surround their house. The play tantalises us with the prospect of murkier revelations... or was he just doing his job?

The play invites us to consider whether it’s fair to pass judgement on the cruelties of the past with the sensibilities of today.

Director Vicky Featherstone appears to have instructed the luxury cast to play every line with the unwavering weight and significance of Pinter, a playwright who came to understand that much more than 50 minutes of such portentousness begins to feel affected and tiresome. THE CANE is also, mystifyingly, performed straight through for over 1 hour and 40 minutes, without an interval, despite being clearly constructed by the writer to have one.

None the less the story and dialogue grip you from the start and the way the playwright drip feeds you information so that your loyalties shift back and forth is every bit as engaging as the finest screen thriller. The actors do full justice to this in their nuanced but merciless portrayal of these horrible people.

Ravenhill creates a house of psychological horrors as the axe marks in the wall testify. Each family member has differing memories of Anna’s childhood, but it seems clear that everyone has been damaged by mum’s post-natal depression, dad's bullying and their off-spring’s violent anger. No one shies away from how much they disliked each other (“you were impossible to love” Anna is told) both back then and up until today.

The coldness between these parents and their child is one of the most shocking elements of the play and something we rarely see portrayed quite so blatantly. The comfortless, austere, living room set, dominated by those axe marks in the 80’s wallpaper and a staircase with its exposed innards suggesting a gaping wound add to the sense of menace, as does a hatch up into the attic through a ceiling which lowers menacingly as we begin to fear what’s up there.

This is a disquieting evening of theatre that asks pertinent questions and dramatises the misery of a lifetime steeped in repressed, fear, anger and hatred.

Latest News

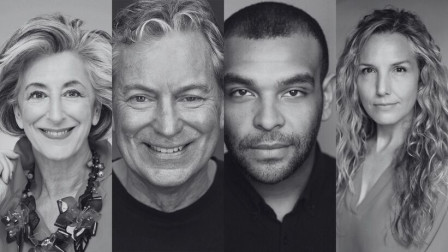

Cast announced for the World Premiere of ALLEGRA

4 February 2026 at 15:02

Cast announced for the World Premiere of ALLEGRA

4 February 2026 at 15:02

Cast announced for European premiere of THE JONATHAN LARSON PROJECT

4 February 2026 at 14:14

Cast announced for European premiere of THE JONATHAN LARSON PROJECT

4 February 2026 at 14:14

Review: LOST ATOMS at Lyric Hammersmith

4 February 2026 at 12:08

Review: LOST ATOMS at Lyric Hammersmith

4 February 2026 at 12:08

I'M SORRY, PRIME MINISTER at Apollo Theatre - Production images released

4 February 2026 at 10:41

I'M SORRY, PRIME MINISTER at Apollo Theatre - Production images released

4 February 2026 at 10:41