Review: FANNY, King's Head Theatre

Ever feel like you’re the only sane one in a family full of nutjobs? Welcome to Fanny Mendelssohn’s world. As the sister of renowned composer Felix Mendelssohn, she’s stuck at home in Berlin with the suffocating pressure to marry, while Felix tours Europe with his musical works…which Fanny wrote.

Charlie Russell as Fanny. Photo by David Monteith-Hodge.

Charlie Russell as Fanny. Photo by David Monteith-Hodge.

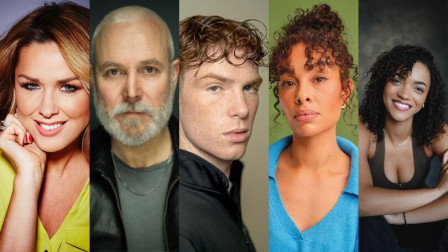

Fanny is one part Bridgerton, one part Pride and Prejudice, with a helping of Laura Wade’s The Watsons and a dash of Max Webster’s current production of The Importance of Being Earnest. Our story begins in 1840s Germany with the Mendelssohn family: selfish, puppyish Felix, bumbling middle brother Paul, and little sister Rebekah, who is played by Daniell Phillips as Kitty Bennet with a bloodthirsty streak. Naturally, their widowed mother (a dryly funny Kim Ismay) is preoccupied keeping the boys out of trouble and getting the girls married off as fast as possible. In the midst of all this is Fanny, portrayed by Charlie Russell in a spellbinding performance. Russell is believable and adorable, sincere and empathetic, as well as funny with both wordplay and physical comedy. She nails an extended audience-participation section, including hilariously working her way around a technical issue on press night, an improvisation which wholly won over the audience.

Towards the end of the play’s first act, the action leaves the confines of the Mendelssohns’ drawing room, as Fanny (both the play and the character) breaks out of their confines and go careering off in unexpected directions. Calum Finlay’s play stumbles through various sub-plots and themes (the Mendelssohn family’s genetic predisposition to strokes is randomly shoved in towards the end. Furthermore, while Fanny explores gender roles and presentations throughout the story, a late-in-the-day monologue hinting at non-binary identities seems tokenistic, and doesn’t fully explore this theme), swerving between slapstick, forth-wall-breaking musical sections, and moments of real pathos. It’s a little chaotic, though that felt intentional in Finlay’s writing, and I rarely felt that the playwright had lost control of the characters and story.

(L-R) Charlie Russell as Fanny, Riad Richie as Wilhelm & Jeremy Lloyd as Paul. Photo by David Monteith-Hodge.

(L-R) Charlie Russell as Fanny, Riad Richie as Wilhelm & Jeremy Lloyd as Paul. Photo by David Monteith-Hodge.

Unlike many stories set in this era, in which the strong-willed heroine must choose between marriage and artistic ambition, Fanny Mendelssohn decides early on that she might as well marry Wilhelm Hensel (Riad Richie). This refreshing narrative choice of Finlay’s means that the story is mostly concerned with if and how Fanny can make the marriage facilitate her musical career. Likewise, Finlay subverts the trope of a Victorian-era husband stifling his wife’s career ambition, instead choosing to make Hensel supportive (though somewhat clumsily so). It’s Felix who, when asked by Queen Victoria, passes off one of his sister’s compositions as his own. However, Finlay presents Felix as more of a shallow opportunist than an outright baddie, and Fanny’s loving, protective relationship with him is central to the story. This offers a more nuanced and realistic depiction of artistic opportunities for women in the 1800s, and of the frustrations, betrayal, compromises and affections which are recognisable in family dynamics, whatever the century.

As well as Finlay’s inventive script and Russell’s charming performance, Fanny is elevated by Sophia Pardon’s set, which, like the story and the title character, is full of surprises. Curtains are ripped down, pianos are leapt over, and there’s a lovely sequence where shadow-puppets are used to evoke a country lane during a carriage ride. Director Katie-Ann McDonough has done a good job in managing the play’s unique tone, and in keeping the story bowling along while also giving breathing space to the moments of pathos and audience participation.

Personally, I could have done with fewer puns (these are a key, and historically accurate, part of Hensel’s character, although it frequently seems like Finlay is stuffing puns into the script for his own enjoyment) and less of a reliance on humour based on rude mispronunciations (though Finlay shows remarkable restraint in only making two jokes based on his protagonist’s first name). Fanny also has a perfectly strong ending without the tacked-on flash-forward coda. Still, Finlay’s fun and fascinating feminist fable has a stellar central performance, and tells an often-overlooked story in a sparking, original tone.

Fanny plays at King's Head Theatre until 15 November 2025.

Latest News

Further cast announced for UK and Ireland tour of Annie

29 January 2026 at 15:10

Further cast announced for UK and Ireland tour of Annie

29 January 2026 at 15:10

The Donmar Warehouse announces programme for 2026

29 January 2026 at 14:30

The Donmar Warehouse announces programme for 2026

29 January 2026 at 14:30

Review: FISH BOWL at Peacock Theatre

29 January 2026 at 13:58

Review: FISH BOWL at Peacock Theatre

29 January 2026 at 13:58

Regent's Park Open Air Theatre announces 2026 season

29 January 2026 at 10:34

Regent's Park Open Air Theatre announces 2026 season

29 January 2026 at 10:34